The following is a guest post by Joshua Sowin. Joshua is a serial entrepreneur and writer currently working on a book about the laws of creativity. He’s the co-founder of SelectHub and blogs at Between Letters. When he’s not chained to a computer, he’s out hiking the mountains of Colorado and traveling the world. You can read more from Joshua at Between Letters and follow him on Twitter as @jpsowin.

Busyness can be a disease for creative work. If we’re not purposeful about it, non-creative busyness will take up our entire lives. Instead of focused work, we’ll spend hours in our inbox, get sucked into click after click on the web, hang out with friends, or whatever’s the distraction of the week.

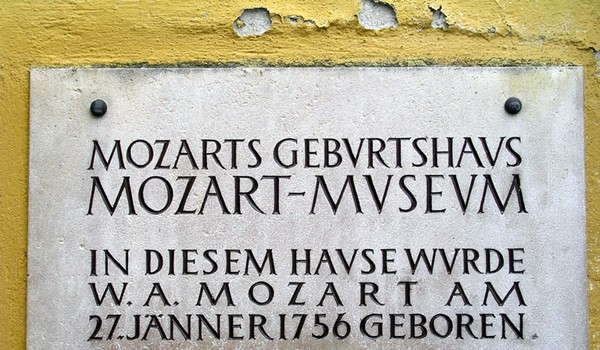

Wolfgang Mozart (1756–1791) may not have had the internet, but he had plenty of other things that could have distracted him from his creative work. He started playing the keyboard at the age of three after overhearing his sister’s lessons. He was obsessed with the instrument and by the age of five he was composing. Granted, it was probably awful, but give him a break — he was writing music while you were still wetting your bed.

Mozart was a child prodigy, but his sister was also very proficient. This gave their father an idea to get rich. He would create a spectacle of his children — he’d show them off on a grand tour around Europe. He would dress them up, the sister as a princess and Wolfgang as court minister with wig and sword, charge for tickets and start living the high life.

Touring can be exhausting even with our fancy buses with electricity and beds and air conditioning. But back then it was much harder. There was the long, bumpy ride to each destination. There was setup and dress-up and practice for the night’s show. And then there was illness — Mozart, his sister, and his father all caught near-fatal diseases.

There were also social commitments. After a show, attendees would invite the family to come to dinners, parties, events, sightseeing, and other gatherings. It would be rude to turn them down. On top of that were the hot young girls throwing their half-naked bodies at the boy. Okay, maybe that’s a stretch.

The point is it’s not the ideal place to get focused work done. It would’ve been easy for Mozart to caught up in the touring life and neglect serious composition.

But he didn’t.

Instead of joining the family on their sightseeing and socializing, he would excuse himself by saying he was sick or too exhausted. When they were gone, he would focus on his music. “His favorite ploy in this vein,” Robert Greene explains in Mastery, “was to attach himself to the most illustrious composers in the particular court they were visiting. In London, for instance, he managed to charm the great composer Johann Christian Bach, son of Johann Sebastian Bach. When the family was invited out on a jaunt, he declined to join them with the perfect excuse—he had already engaged Bach to give him lessons in composition.”

By having the self-discipline and strategy to turn down busyness, Mozart was able to focus deeply on his music and learn from the greatest composers of his era.

If a young boy can do this, why can’t we?