The following is a guest post written by Michael Rank. He is a doctoral candidate in history and the author of 12 books and host of the History in Five Minutes Podcast. His new book is called The Most Productive People in History: 18 Extraordinarily Prolific Inventors, Artists, and Entrepreneurs, From Archimedes to Elon Musk

Benjamin Franklin was nothing if not diversified in his talents. The Founding Father was a printer, scientist, inventor, diplomat, postmaster general, educator, philosopher, entrepreneur, library curator, and America’s first researcher to win an international scientific reputation for his studies in electrical theory. He even made contributions to knowledge of the Gulf Stream.

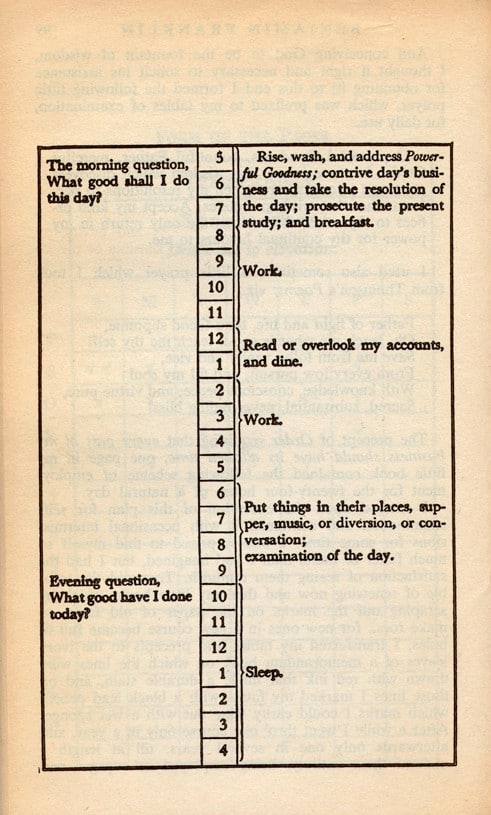

How did he do it? By keeping up a highly structured daily schedule and tracking the results. Franklin considered personal productivity to be a moral duty. It is for this reason he talks in detail about his daily habits in his autobiography. No part of the day was left without marching orders. It all began with a simple question each morning: What good shall I do this day? From then on, he answers that question with the particulars of each moment:

- 5-7 am: Rise, wash, and address Powerful Goodness; contrive day’s business and take the resolution of the day; prosecute the present study; and breakfast

- 8-11 am: Work

- 12-1 pm: Read or overlook my accounts, and dine

- 2-5 pm: Work

- 6-9 pm: Put things in their places, supper, music, or diversion, or conversation; examination of the day

- 10 pm – 5 am: Sleep. Before then, answer the question ‘What good have I done today?’

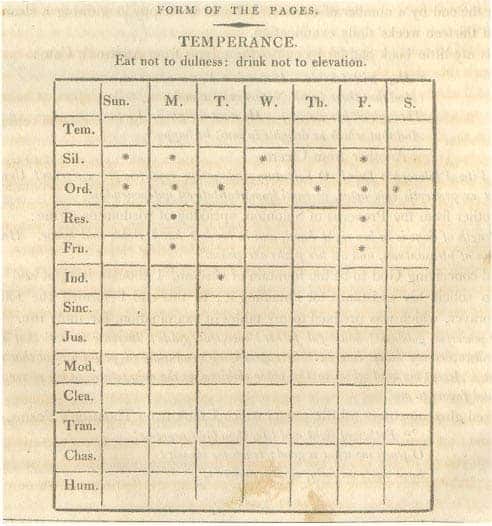

Franklin believed that such schedule-keeping and note-taking could do more than create a productive day. It could also create a completely moral life. In his readings, he identified virtues that were common across Western Civilization. Writers across history and cultures came back to these virtues. He narrowed them down to 13 and developed a 13-week plan of moral improvement. He committed to giving strict attention to one virtue each week. Franklin kept a book of 13 charts, with a virtue at the top of each chart. Each chart had a column for each day of the week and 13 rows for each virtue. At the end of each day, he put a mark next to each one he did not uphold.

His goal was to eventually have a clean chart. This would ultimately rid him of bad habits.

Here are his 13 virtues:

- Temperance.

- Silence.

- Order.

- Resolution.

- Frugality.

- Industry.

- Sincerity.

- Justice.

- Moderation.

- Cleanliness.

- Tranquility.

- Chastity.

- Humility.

Franklin was practical enough to know that tackling all 13 virtues at the same time would lead to discouragement and failure. He took them on one at a time, only moving on when a virtue row was blank. He was like a gardener, who does not attempt to kill all the weeds at once, but works on one bed at a time. In this way, he would progress through his virtues checklist.

Franklin put together perhaps a more comprehensive plan for productivity and moral improvement than anyone else of his time. But did it work? Yes, but not as quickly as he thought it would. His first full cycle of the 13 virtues took a full year instead of 13 weeks. And he only did this cycle once in several years, not four times a year as he originally supposed.

He never arrived at perfection, but he was glad that he undertook the endeavor in the first place. Franklin credited attempts at Temperance to living to a ripe old age; to Industry and Frugality for earning his fortune; and to Sincerity and Justice for earning the confidence of his country. He wrote that it was better to undertake the experiment and fall short than to not try at all.

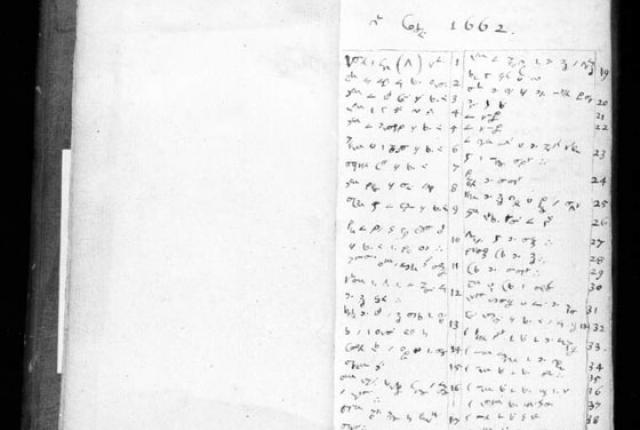

Perhaps the only historical figure to challenge Franklin in his rigorous use of note-taking is Isaac Newton. It is for this reason that Newton, the inventor of classical physics and calculus, was such an effective scientist. He organized his research through meticulous record keeping. He kept track of his theoretical analyses by producing up to 100 pages of notes a day. The Newton Project, a digital humanities research project, has catalogued 4.2 million published and unpublished words by Newton, many of which are made available as downloadable interactive transcriptions. They are a densely written collection of writings in physics, mathematics, and theology.

Newton’s habit of note-taking began at a young age. He shared Benjamin Franklin’s belief that recording one’s poor behavior could lead to self-improvement. Among his early entries is a list of 49 sins that he admittedly committed before “Whitsunday.” His list reveals a deeply pious man who struggled to reconcile his irascible nature with a commitment to obedience before God. Some of his confessions included:

- Using the word (God) openly

- Eating an apple at Thy house

- Making a feather while on Thy day

- Denying that I made it

- Making a mousetrap on Thy day

- Contriving of the chimes on Thy day

- Squirting water on Thy day

- Making pies on Sunday night

- Swimming in a kimnel on Thy day

- Putting a pin in Iohn Keys hat on Thy day to pick him

Many of these “sins” appear so trifling as to border on the ridiculous. But whatever our judgment on the pernicious nature of “squirting water on Thy day,” Newton’s record keeping had surprising results. His recording of his own sins apparently had a positive effect on his character. He repeated the process after Whitsunday and recorded only nine sins. While he never achieved moral perfection in life, he used the same concept of note-taking-as-moral-improvement as Franklin did a century later. Recording his own behavior made him aware of his actions, resulting in less self-diagnosed bad behavior.

While few of us will ever approach the heights of productivity reached by Franklin or Newton, we can be inspired by their data-driven approach to producing results, whether in our professional or personal lives.